The Power of Place: Unleashing Census Data in Your Tableau Analytics

Kevin and I are incredibly excited to have Sarah Battersby join us today as for another guest blog (if she keeps writing for us, we may have to make her an honorary Flerlage Twin!!). Sarah has been a member of Tableau Research since 2014. Her primary area of focus is cartography, with an emphasis on cognition. Her work is focused on helping everyone to visualize and use spatial information more effectively—without the need for an advanced degree in geospatial. Sarah holds a PhD in GIScience from the University of California at Santa Barbara. She is a member of the International Cartographic Association Commission on Map Projections, and is a past President of the Cartography and Geographic Information Society (CaGIS). And, perhaps her greatest skill—she can identify Kevin and Ken correctly 50% of the time! Sarah can be contacted at sbattersby@tableau.com or on Twitter @mapsOverlord.

Problem: You have a ton of

US data—and it has a spatial aspect to it. It’s easy to map your data in

Tableau, but you want to know more detail about the geographic locations where you have lots of data. Maybe you want to

know about the total number of people and their race or socioeconomic status?

Or the median income or age? Or how about level of education? The US Census

tracks all sorts of social, economic, housing, and demographic details about

the US population, but it can be hard to collect it all and get it into

Tableau. Especially if you want the data at fine detail (e.g., Census Tract)

and for large areas (e.g., more than one state).

Let’s fix this

problem!

In this post, I will discuss methods for collecting Census attributes and geographies to use in Tableau.

We’re going to get into a bunch of different technologies along the way, but

don’t let this stress you out. In most cases, you won’t need all of this. My

goal is simply to give you everything you might

possibly need in order to collect and map this data.

Collecting

Attributes

You

can always download attributes as individual tables from the census website but, if you want

a lot of data, it might be easier to use the Census API and some code to

automate the data collection. The Census API provides a

programmatic method for accessing a number of their data products. It lets you

directly tap into datasets by specifying the product, the geography, and the

attributes. When you use Python (or the language of your choice) to automate

your calls to the API, you can collect large quantities of data, combine it

together, and write it to an output file (e.g., csv file) in one fell swoop. To

that end, I’ve written a Jupyter

Notebook (basically

an interactive file that contains code, images, and narrative text) which

contains all the code as well as detailed descriptions of what we are doing at

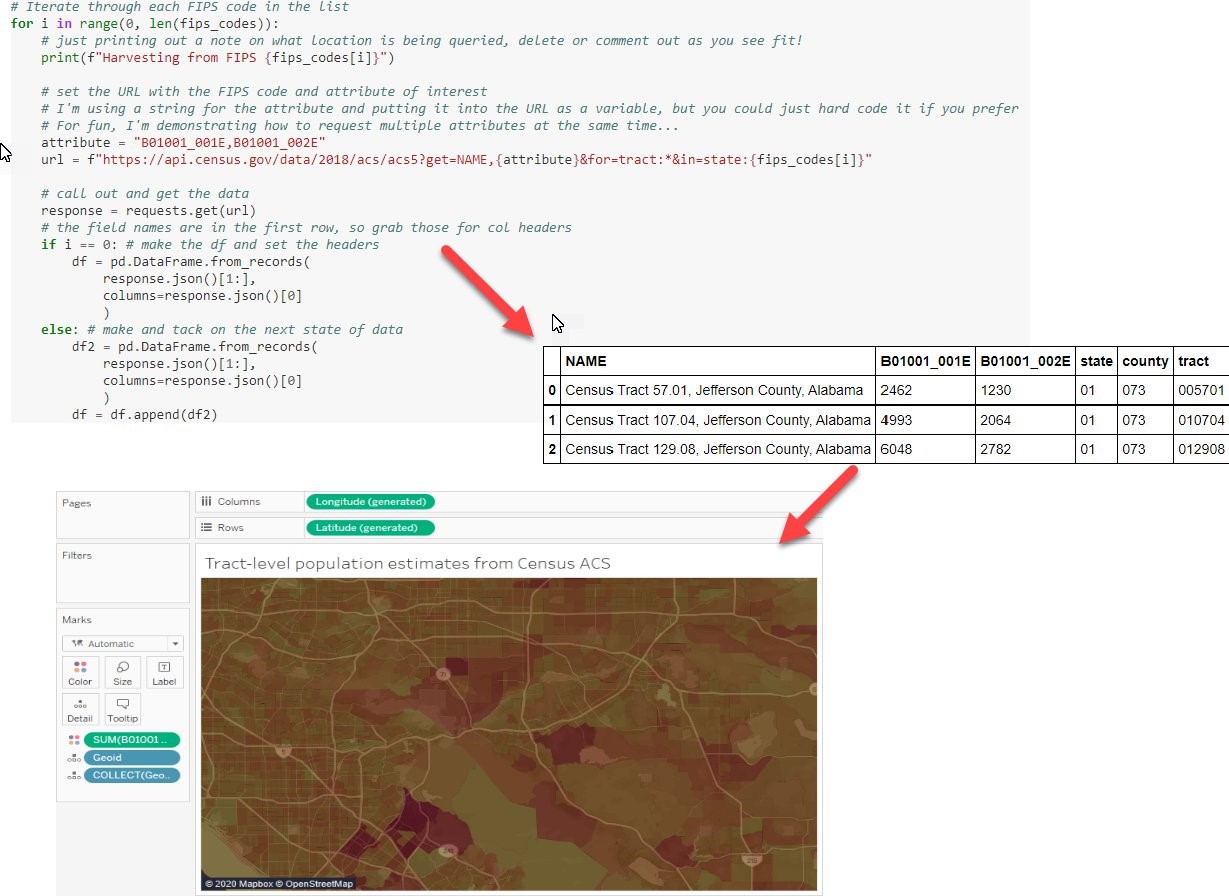

each step. The basic process that the notebook takes is to iterate through

calls to the API until we collect everything we need, after which we write the

data to a csv file, which we’ll use in Tableau.

Mapping

State/County in Tableau

If

you’ve run through the Jupyter notebook, then you now have all your attributes

in a csv file. If those attributes are at the county or state level,

you can map those directly in Tableau using the built-in geocoding. We won’t

need any fancy spatial files or anything like that.

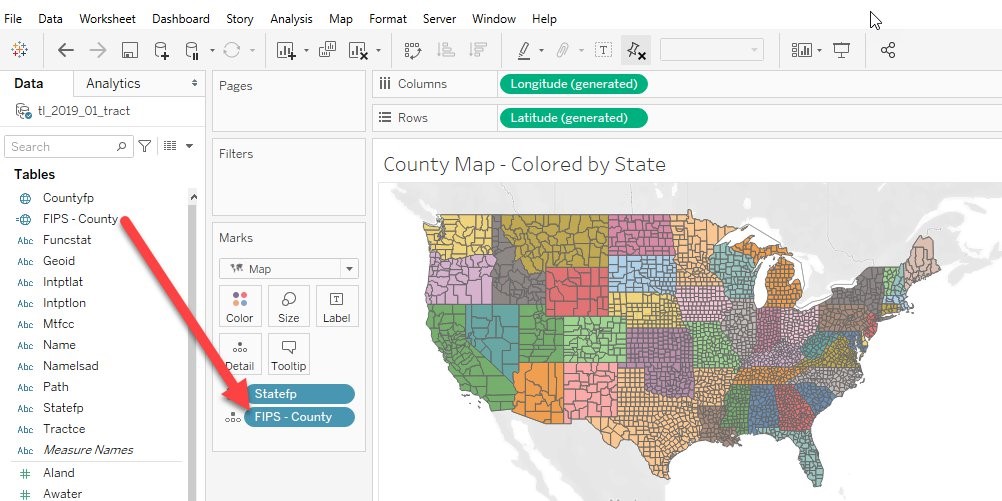

If

you have states, then all you need is the state name. Counties, on the other

hand, can be mapped with a county name/state name

combination OR with the 5-digit FIPS code. This code is just a combination of the 2-digit state FIPS code (e.g., 01

is the code for Alabama) and the 3-digit county FIPS code (e.g., 001 in Alabama

is Autauga County). You should have all of this information with the data you

downloaded. The trick is to make sure the FIPS codes are defined as strings (or else leading zeroes

will be truncated), and then make sure you have them

combined into a single 5 digit FIPS code (e.g., 01001

is the 5-digit code for Autauga County, AL).

Once this is in Tableau, just be sure to make sure the field’s

geographic role is set to “County”.

Different Levels

of Detail

If

you are mapping at another level of detail (e.g., census block, block group,

tract, etc.) you will need to download the spatial boundary files from the

Census. Fortunately, they’ve made all of this data available online. If you

just need a few files, it’s easy to download them from the Cartographic

Boundary Files

page. There will often be different files for different years (census tracts,

for example, change with each decennial census) so make sure the year you

download aligns with the year of your data.

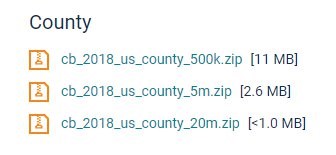

Another

thing to consider is the level of spatial detail (generalization) of the

spatial file. For instance, you can download US

Counties as a 1:500k, 1:5m, or 1:20m file.

The more generalized, or simplified, the geographies, the smaller

the file—the 1:20m file is less than 1MB in size, while the less

generalized/more detailed file at 1:500k is

11MB. Tableau will have to work harder to process the more detailed

files, so choose the one that meets the level of detail you need in your

visualization.

Using the Census

FTP Site

If

you need a lot of spatial files—for instance, all Census tracts for 10

different states— you can use the Census FTP site to collect all of the files

you need at once, rather than downloading them individually. Here’s how:

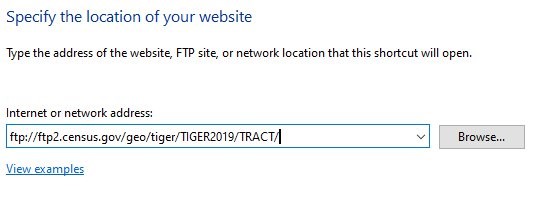

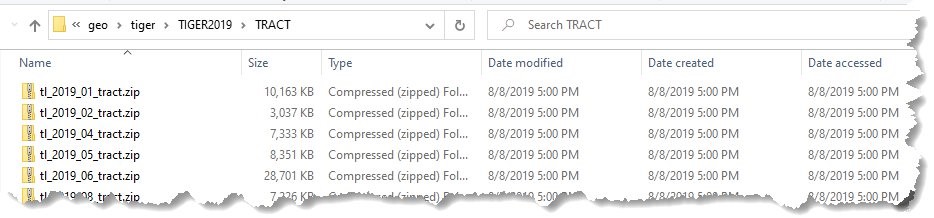

Connect to the Census FTP server and find the data. The 2019 TIGER

data can all be found here. For

Census tracts (TIGER 2019 data), I use my Windows file explorer to add a

network location of ftp://ftp2.census.gov/geo/tiger/TIGER2019/TRACT/

This

takes me to a directory with zip files for the tracts for each state. I can

select all of the states that I want and copy all of the files I need to my

local drive. You will need to know the state FIPS codes as the end of each file

contains that code, rather than the state name (you can find a list of FIPS

codes here).

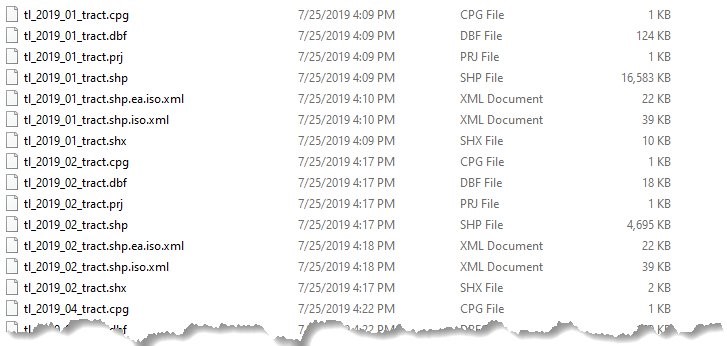

With the zip files on your local drive, select them all and

unzip them. I like 7-Zip

since it lets me easily unzip lots of files

at once, but you can use whatever software you like, including the one that is built into Windows. Whatever you use, you’ll most likely end up with a separate folder for the geometry for each

unzipped file. To make your life easier, it’s good to move all of the files

into the same parent folder (that makes combining/unioning them easy in Tableau

or GIS).

I use Windows, so I will tell you how I do this from a Windows command line. I’m sure you can do the same on a Mac and I’m

sure that Mac users will tell me how infinitely better that method is :) All I

can say is that if you use a Mac, just use Google to figure out how to move a

bunch of files easily.

I unzipped all of my data into a single directory. Then, using the command line, I first change to that directory.

Next, I use a simple statement to recursively walk

through each folder in the directory and move the files to a new directory

located at C:\temp\Census - tiger\tracts_all\.

FOR /R

".\tracts" %i IN (*) DO MOVE "%i" "C:\temp\Census -

tiger\tracts_all"

We

now have a nice, single location with every freakin’ part of every freakin’

shapefile for Census tracts in every freakin’ state. That’s 357

files!

Note: If you’ve

used the Jupyter notebook then you may already be adept with Python. In that

case, then feel free to do the above in Python if you wish.

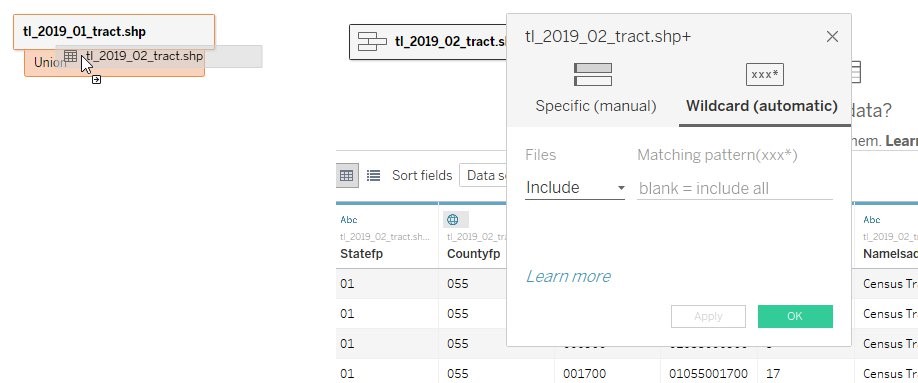

Combining the

Files in Tableau

To combine all of these files together, you can add all of these shapefiles in Tableau and union

them together using Spatial

union in Tableau,

which is new to 2020.3. Just create a wildcard union then

create a hyper extract. It’s important to note

that these files can be quite big when you’re

working with small geographies over a large space—for instance, an extract containing all Census tracts for

all US states is a 200MB file!).

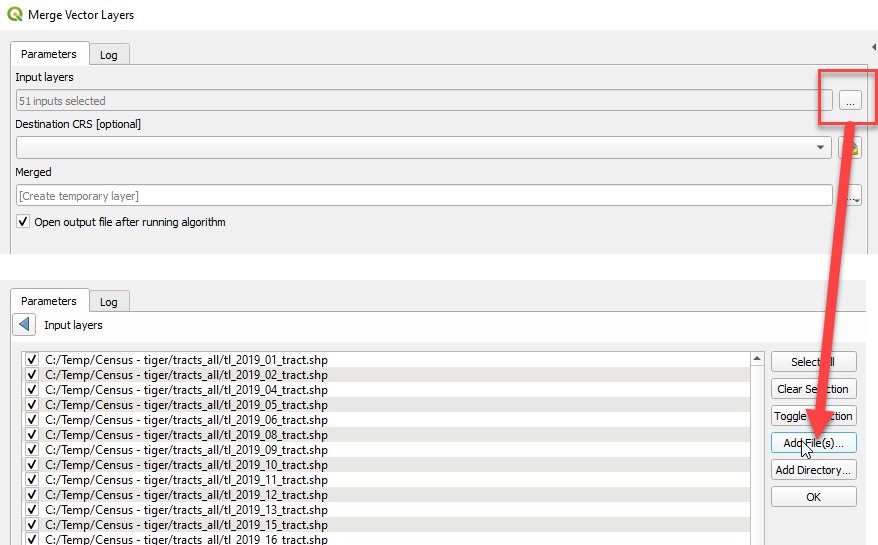

Combing the Files

in GIS

If

you’re still on a pre-2020.3 version of Tableau, then you can use a GIS, such

as the free/open source software QGIS, to union the files together. Just use

the Vector Data Management tools to merge vector layers. You can click on three

dots next to ‘Input Layers’ and add all of the *.shp files in the directory

where you unzipped your shapefiles.

Small

geometries come in as fairly detailed polygons—and as really big files so you may wish to simplify them a bit. A

great tool for simplifying the geometry is the online software, MapShaper.

Once you have your geometries collected (and combined together, if needed) you

can use MapShaper to quickly and easily simplify them.

So,

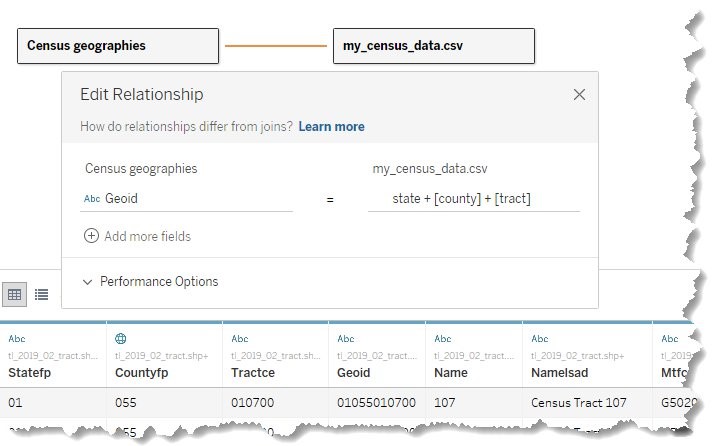

we now have all of our attributes and we’ve combined and simplified all of our

geographies. The only thing left to do is join them together in Tableau. Once

we’ve done that, we’re ready to map away!!

Wrap-Up

Okay,

I know that I just threw a lot at you—we talked about Python, Jupyter

notebooks, APIs, FTP sites, command line, and GIS tools. Fortunately, it’s

likely that you won’t have to use all of this every time you need to collect

census attributes. For instance, smaller projects may only require the Python

code and Tableau. However, if and when you find yourself in a situation where

you need lots of different attributes for lots of different geographies, I hope

that this post acts as a helpful guide for the tools and steps you’ll need to

take to go from idea to amazing Tableau map! Thanks for reading!

Sarah Battersby

March 8, 2021

Hello Ken, can we get spatial files of another countries?

ReplyDeleteThis blog is focused on getting info from the US Census website, so the above is focused on the United States. However, other countries likely have similar sites you can use to obtain spatial data.

Delete